It’s a tough time to be an American climate realist. After all, which realism will you choose? The Beltway realism that limits U.S. commitments, and even U.S. initiatives, to those that are immediately sustainable by veto-proof congressional majorities? The internationalist realism that begins instead with the recognition that – as the recent multilateral climate talks in Bali clearly indicated – a viable global accord will necessarily require substantial rich-world financial commitments? How about a straightforward scientific realism that proceeds differently, ignoring the politics of the moment and stressing instead the physical demands of the climate system?

Ideally, there would be at least one realism to satisfy everyone. But this is not an ideal world. It’s certainly not an ideal country. If it were, the United States wouldn’t have repudiated the Kyoto Protocol, which way back in 1997 asked us to reduce our emissions to 7% below 1990 levels by 2012. Had we done so, today’s projections wouldn’t show our 2012 emissions being a full 20% higher than they were in 1990. Had we done so, we wouldn’t now find ourselves facing some extremely unappealing choices.

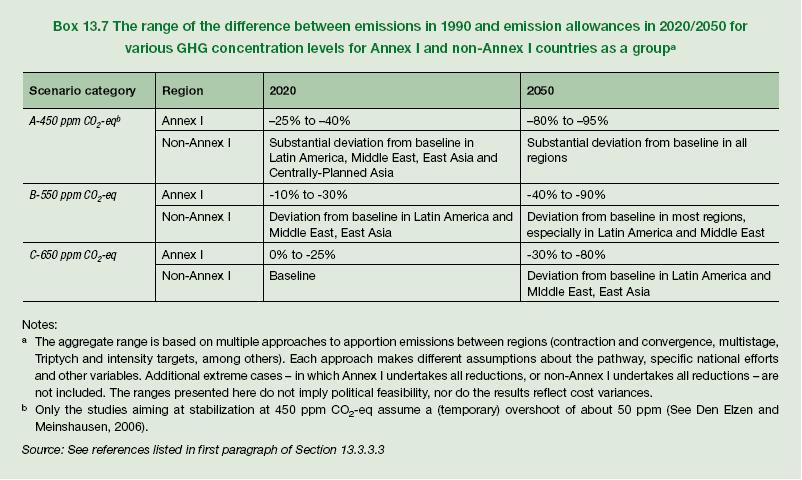

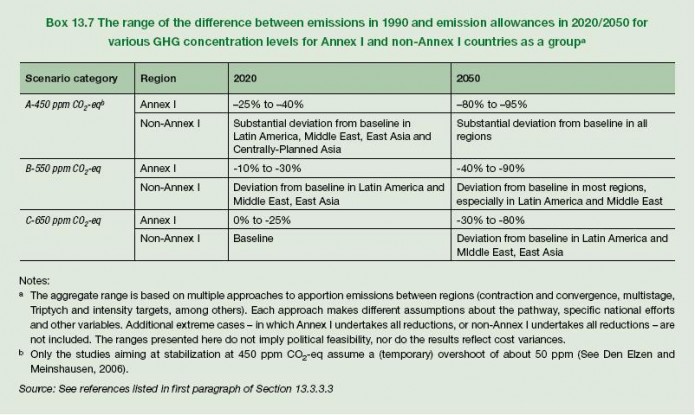

So, what are we to do? First, we should be clear that the climate system is not particularly responsive to political calculation. Its realism is a physical one, and we know it, if we know it at all, only though science. Which is why it’s important to remember that the Bali call to reduce emissions 25-40% below 1990 levels by 2020 hails from Box 13.7 in the Working Group III volume of the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report:

Second, we should be honest about the drift of the science, which is very bad. In fact, the 25-40% 2020 Annex 1 reduction target that was in such high-profile contention in Bali comes from the IPCC’s most stringent scenarios – the top line in the table above – which was the closest it could get, in the Fourth Assessment Report, to the emergency trajectory we actually need. This is a long story , but its bottom line is that we should be thinking in terms of the high end of Bali’s 25-40% reduction range, not the low end, at least if we want a decent chance of holding the total warming to 2ºC above pre-industrial levels (today’s usual, dangerously high, benchmark for the maximum manageable warming).

Third, we should be brave enough to draw some anything-but-reassuring conclusions about the current crop of national climate legislation. Even the Sanders-Boxer-Waxman trajectory – as defined in the best of the legislation now in play in the United States – calls only for a return, by 2020, to 1990 emissions levels. This is far, far less than the call for a 25-40% reduction that focused so many minds in Bali, and its adoption as official U.S. policy would seriously undermine, if not actually poison, the international negotiations. Even worse, such a low U.S. target is entirely inconsistent with the global emergency stabilization program that, frankly, we need as soon as humanly possible.

U.S. Obligations

Weak targets are just the first part of the problem. The second is obligations. It’s now abundantly clear that carbon markets, whatever else they may or may not be able to do, are definitely not, in themselves, capable of meeting the financial challenges of an internationally viable climate regime. Moreover, this is obvious no matter your strategic preferences. If you’re most concerned about the fate of the poor and the vulnerable, then you want to know where hundreds of billions of dollars in adaptation funding is going to come from. If mitigation is your key issue, you want to know how the best available technology is going to be rapidly dispersed around the world, and you suspect that, however it’s finally done, it’s not going to be cheap. If forest protection is your priority, then the question is how you’re going to support the initiatives necessary to forestall massive deforestation. And if you’re already panicked, and ready to start pumping streams of money into carbon sequestration, then it’s not unlikely that you’ve also begun to wonder just who’s proposing to pay the bill.

I am not claiming that we can’t afford to save the world. Rather, I’m simply arguing that it’s long past time to start thinking strategically about money. More particularly, it’s past time to admit, and this despite all the techno-optimism in the world, that stabilizing the climate is not going to be cheap, and then to draw some obvious – and realistic – conclusions.

One obvious conclusion is that we can’t afford to give away gobs of money to corporations. Yet we’re very much in danger of doing just this, and soon. The authors of the Lieberman-Warner bill propose to launch the age of U.S. federal climate legislation with a giveaway of almost 80% of total permits – a massive, perhaps unprecedented corporate giveaway. They further propose to reduce that giveaway so slowly that decades upon precious decades would pass before the windfall fades and the auction revenue stream widens enough so that low-income transition assistance, renewables and energy efficiency subsidies, adaptation funding, “cap-and-dividend” style citizen rebates, forest protection, technology transfer support, and all the rest of the necessary transition programs have some hope of adequate funding.

But even when both Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama have announced their support for 100% auctioning, many of the big Washington environmental groups are still supporting such corporate giveaways. And they’re doing so even though, to quote a congressional staffer who requested anonymity, Lieberman-Warner is increasingly looking like “the best deal that American business will ever get.” Why? Because they’re pursuing their own, preferred version of realism. Environmental Defense, for example, argues on its website that Lieberman-Warner is necessary because it’s possible now: “if we wait just two years to enact the bill or something similar, we’ll need to double the pace of emissions cuts to get where we need to be in 2020.” This is an exceedingly odd claim. Whatever numerical analysis lies behind ED’s “if we wait just two years” claim, it’s designed to justify Lieberman Warner’s fatal political compromises, and thus its disastrous financial architecture, by means of bold claims for a 2020 target that is patently inadequate.

And things get worse. Even if we step beyond today’s Beltway realism and adopt domestic emissions reduction targets commensurate with Bali’s 25-40% range, or, better, even if we focus on the top end of that range – 40% by 2020, which is about right for wealthy countries like the United States – and even if we achieve those targets, this would hardly be the end of our national obligations. The United States must also shoulder international obligations commensurate with our carbon debt (historical responsibility) and our capacity to pay. Looking toward the future, we have to consider our share of the wealthy world’s obligation to provide the funds and technology necessary for the developing countries to achieve what the IPCC (look under 2020 in the above table) called “substantial deviation from baseline” emissions. And that’s not to mention our share of the adaptation burden.

Looking Ahead

There is a way forward. We have the technology. And we have the money. After all, the United States is spending at least $2 billion dollars a day on the military. But if we’re going to engage the climate crisis in an environmentally adequate and politically viable manner, we need to find a path forward that satisfies all the “realisms” noted above. And the undeniable fact that this would be one of the hardest things we’ve ever done is no excuse for pretending that it’s not necessary.

Fortunately, we’re getting closer. But the hour is late, and we can’t take anything for granted. The time now, inevitably, has to be one of preparing as well as one of acting. Because the scientific ground for the necessary emergency mobilization has been prepared, but not the political ground. And the problem? That the only way the Non-Annex 1 countries are going to make a “substantial deviation from baseline” emissions paths, in time, is if the wealthy countries provide them with the technology and development assistance necessary to do so without compromising their development prospects. Politically this can only happen in a progressive manner (not in the sense of “progressive politics” but in the sense of “progressive tax”) as part of a package that mobilizes the longing for economic justice as well as the drive for climate stabilization. In other words, we need a new deal that’s not limited to climate protection, but also reforms “development” and drives poverty alleviation in the wealthy world as well as the poor.

Green collar jobs are part of the answer. So is the solar revolution. So is “cap and auction” (as against “cap and grandfather”). So is the new flexibility that was visible in Bali (though not from the United States). But they’re not enough. We also need a new realism, one that doesn’t ask either science or the poor to step aside in the interests of short-term calculation.

It won’t be easy, but it’s the only real chance we have.