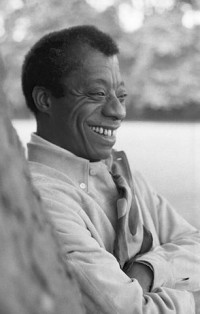

(Photo: Wikipedia Commons)

It’s hard not to feel overwhelmed sitting in the theater watching I Am Not Your Negro, the culmination of ten years of work by filmmaker Raoul Peck on the life and thought of James Baldwin, the great writer and social critic of the mid 20th century. The director’s blending of Baldwin’s work and words with footage of today’s racial unrest left me wishing — at many moments — I could hit pause and replay.

Plenty of professional film critics have commented on this new film’s timeliness and cinematic brilliance. The New York Times, for instance, calls it a “90-minute movie with the scope and impact of a 10-hour mini-series.” The film’s decades-old footage does indeed come across as remarkably current and clairvoyant, almost as if Baldwin himself were speaking from the grave.

The film focuses most of its energy on Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript Remember This House, a 30-page essay on the deaths of civil rights heroes Medgar Evans, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. Director Peck weaves into his treatment of this manuscript footage of Baldwin’s public appearances and snatches of Hollywood’s early depictions of race.

Baldwin speaks directly to the white moderates of his time who, no different than today, watch the atrocities against black and brown people play out on their televisions but feel unaffected.

“I’m sure they have nothing whatever against Negroes. That’s really not the question,” we hear Baldwin argue. “No, the question is really a kind of apathy and ignorance, which is a price we pay for segregation. That’s what segregation means, that you don’t know what’s happening on the other side of the world because you don’t want to know.”

The segregation that Baldwin so insightfully explored remains ever-present today. About 18 percent of America’s public schools currently rate as “hyper-segregated,” with over 90 percent of their students minorities. In 1988, only 6 percent of schools nationally fit in this “hyper-segregated” category.

Not facing realities like these does not make them go away, and I’m Not Your Negro reminds us — in no uncertain terms — that in many ways we have made virtually no racial progress at all. The racial wealth divide today — the gap between black and white families — has not decreased, in fact, since James Baldwin died in 1987.

If average black family wealth continues to grow at the same pace of the past three decades, black families will have to labor 228 years to amass the same amount of wealth white families already have today. Those 228 years amount to a span of time just 17 years shorter than slavery’s 245-year American lifespan.

But this film addresses more than race. It’s about class, too. Both Malcolm X and Dr. King, Baldwin points out in his unfinished manuscript, were thinking deeply about class by the time of their deaths.

Both giants, Peck notes, were going beyond the race issue because they saw race as just “one side of the battle.” They were concentrating more and more on power and how classes reproduce themselves.

“If you’re born rich, you have a 99 percent chance to stay rich,” as Peck puts it. “If you are born poor, you have a 99 percent chance to stay poor.”

In Baldwin’s words: “White is a metaphor for power, and that is simply a way of describing Chase Manhattan Bank.”

Baldwin’s prophetic assignment to white viewers remains as relevant as ever.

“Why was it necessary to have a nigger in the first place?” he asks. “Because I’m not a nigger, I’m a man. But if you think I’m a nigger, it means you need him. And you better find out why.”

Baldwin’s question speaks to the 1994 crime bill that led to mass incarceration, to the tax and Wall Street “reforms” of the Clinton and Bush years that concentrated wealth into fewer (and whiter) hands, and to the election of Donald J. Trump. Answering that question could hardly be more critical to our shared future.

“The future of the Negro in this country,” Baldwin concluded, “is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country.”

At their peak of their influence, Malcolm, Martin, and Medgar still hadn’t reached the age of 40, a point that should give us hope for the rising millennials who hold significantly more progressive views than their elders. This film, one hopes, will inspire many more of them into action that would do James Baldwin proud.