"Economics, as it has been practiced in the last three decades, has been positively harmful for most people." ~ Economist Ha-Joon Chang

For over thirty years we've treated something as fact which is actually false. Economists we trusted to know better didn't, and so people have suffered and continue to suffer. This pernicious economic myth is the idea that a rising yacht lifts all tides, or as more popularly described, "trickle-down economics." If we are to start running our economy in a way we could one day describe as notably less insane, we must finally come to see it for what it actually is.

An Undead Idea

This belief -- that it's good economics to give a relatively greater and greater share of the pie to the top of the economic spectrum because the absolute sizes of all remaining shares will grow -- has taken some mortal hits in recent years by some major players, most notably even the OECD and IMF. In fact, it has now reached the point such that the idea being left alive in the minds of anyone makes it a good candidate as an extra in The Walking Dead.

This belief -- that it's good economics to give a relatively greater and greater share of the pie to the top of the economic spectrum because the absolute sizes of all remaining shares will grow -- has taken some mortal hits in recent years by some major players, most notably even the OECD and IMF. In fact, it has now reached the point such that the idea being left alive in the minds of anyone makes it a good candidate as an extra in The Walking Dead.

Surveying the data, we'll start with Wall Street bonuses versus the economic multiplier effects of higher velocity money, go on to economic growth research in relation to distributional inequality, and end with what we know from global cash transfer evidence and the economic effects of billionaires. Let's burn this undead idea of inequality-driven economic growth with napalm and bury it in concrete, shall we?

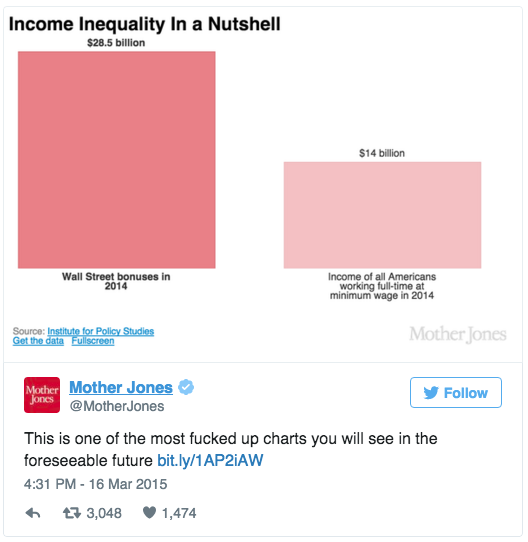

This chart alone is perhaps enough to warrant a trip to the nearest window to shout out, "I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!"

Wall Street earned twice as much in year-end bonuses alone as all full-time minimum wage workers combined earned the entire year.

What Mother Jones neglected to mention however is something that goes well beyond "fucked up," and something which did not go unmentioned in a piece by the Institute for Policy Studies after identical news the year before.

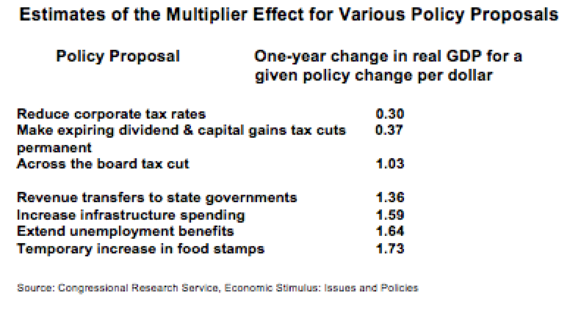

Every extra dollar going into the pockets of low-wage workers, standard economic multiplier models tell us, adds about $1.21 to the national economy. Every extra dollar going into the pockets of a high-income American, by contrast, only adds about 39 cents to the GDP. These pennies add up considerably on $26.7 billion in earnings. If the $26.7 billion Wall Streeters pulled in on bonuses in 2013 had gone to minimum wage workers instead, our GDP would have grown by about $32.3 billion, over triple the $10.4 billion boost expected from the Wall Street bonuses.

Yeah, you read that right. In 2013, by giving huge bonuses to those on Wall Street instead of low-wage workers, we actively prevented the creation of about $22 billion in additional national wealth. In 2014, we did the same thing, but to an even larger degree, preventing about $23 billion in additional national wealth that would have otherwise been created, had those billions in bonuses been distributed to low-income earners instead.

Year after year, we prevent new wealth creation. Why is this the case? What causes such a big difference in wealth creation, such that money at the bottom is over three times more effective at driving economic growth than money at the top?

Well, economists call it the "multiplier effect" whose origins are in what's called the "marginal propensity to consume." It describes how those with little money spend it quickly and those with lots of money don't.

Fast Money vs. Slow Money

Simply put, monetary exchanges have a frequency rate -- a "velocity" -- and this rate is far higher at the bottom than at the top. When you have a lot of money, each individual dollar, for the most part, just kind of sits around. Sure, it may be put to use eventually, but these dollars are more like gold coins inside Scrooge McDuck's bank vault. Occasionally they get swam in, but they're really just there to be counted and look shiny. Additionally, they can even get sent overseas to sit around in vaults elsewhere.

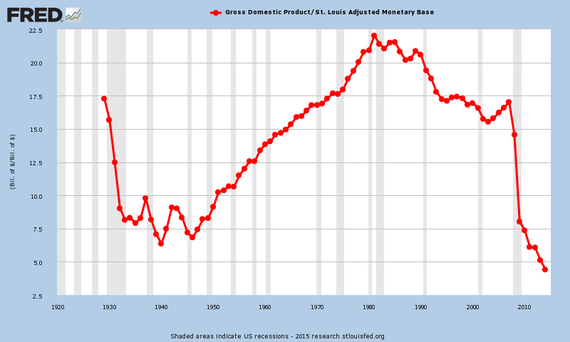

Looking at the latest money velocity charts and comparing today's numbers to the historical record is all one needs to see what happens to the overall rate of market exchanges when we start letting the top accumulate more and more of the total money supply.

We are exchanging the dollars in our money supply more slowly than even during the Great Depression. The result has been an economy growing more and more tilted every day, such that even Disney itself, a company built on middle class consumption, is actively leaving it behind in an accelerating sprint towards that shrinking population with money to spend in greater and greater amounts.

The velocity of each dollar in our total money supply is now lower than has ever been recorded in all of U.S. history.

Meanwhile, that shrinking amount of money that's still accessible in hands at the bottom? It's changing hand after hand, and quickly. That dollar is no coin in a bank vault. It helps buy a gallon of milk, which pays a cashier, which helps buy a haircut, which pays a hair stylist, which helps buy a ticket to a movie, which pays a concession stand worker, which helps buy a dinner for two, and on and on it goes, like a fiery hot lava potato.

Source. CRS

Section 2: Subtraction and Addition

It's not just that someone with little money has enough money to spend that expands an economy. The most effectual part is that a dollar is also removed from the hand overflowing with dollars. Who knew Robin Hood oversaw such an effective economic stimulus program? But that's how it works and also in a way that stabilizes the entire economy according to a new model built by Ricardo Reis and Alistair McKay of Columbia University and Boston University.

"It's the redistribution that has a lot of kick," Reis said in an interview with Bloomberg. "The usual argument for transfers is basically Keynesian. We find that has very low impact in our model."

According to Reis and McKay, there is no better way of creating a more stable economy than to expand tax-and-transfer programs that specifically reduce inequality, like food stamps and social insurance.

A healthy economy is not one of extreme inequality, but one where everyone has enough money to spend into it, to the point they can start saving what they don't need to spend.

When the only ones capable of making exchanges are a small percentage of the population, the entire economy suffers because the many are excluded for the benefit of the few, but this benefit too is an illusion. There is no real benefit. Pretending otherwise is like thinking that cutting off the blood in your body to everything except the brain is good for business. It's not. It's good for gangrene.

OECD Findings

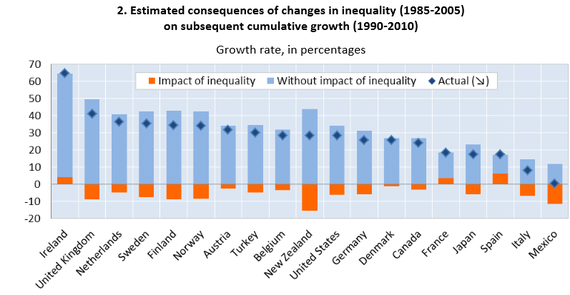

In a December 2014 report titled, "Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth," the OECD found that inequality slows economic growth.

"Rising inequality is estimated to have knocked more than 10 percentage points off growth in Mexico and New Zealand over the past two decades up to the Great Recession. In Italy, the United Kingdom and the United States, the cumulative growth rate would have been six to nine percentage points higher had income disparities not widened, but also in Sweden, Finland and Norway, although from low levels. On the other hand, greater equality helped increase GDP per capita in Spain, France and Ireland prior to the crisis.

One sentence from the report stands out in particular, as something absolutely vital to focus on to achieve strong economic growth.

The impact of inequality on growth stems from the gap between the bottom 40 percent with the rest of society, not just the poorest 10 percent. Anti-poverty programs will not be enough, says the OECD.

It is not enough to tax and transfer only from the top to the bottom.

Transfer recipients must include at least about half of the entire population. The incomes of the middle class must be increased alongside those living under or near the poverty line, and all of this entirely at the expense of the top. By not doing this, we all lose, even the rich.

Between 1990 and today, US GDP grew from $6 trillion to what is now almost $18 trillion. The OECD is saying that had we not allowed our inequality to grow alongside it, our GDP would have grown an extra trillion dollars. And had we reduced our inequality, our GDP would now likely be somewhere north of $20 trillion instead of $17.7 trillion.

But we didn't do that. We instead shoveled money hand over fist into the pockets of those with already overstuffed pockets, and to this day we continue to do so. However, this behavior is beginning to be questioned by even more growth experts than the OECD. The IMF is now asking them too.

IMF Findings

In June of 2015, the International Monetary Fund upped the ante with an even more damning report on the effects of income inequality on economic growth than the OECD.

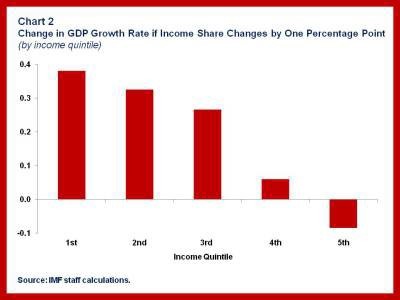

Source: IMF

According to the IMF, increasing the share of the total pie of the top 20% by just 1% (by, say, throwing bonuses at them) decreases economic growth by 0.08 points. It actually damages the economy. Overall wealth decreases. On the other hand, increasing the share of the bottom 20% by the same 1%, increases economic growth by 0.38 points, that makes it five times more effective and in the direction we actually want. Similar growth increases are seen in decreasing amounts for the middle three quintiles, with 0.33 points, 0.27 points and 0.06 points respectively.

In other words, transferring money from the bottom to the top actually slows GDP. It erases national wealth. It shrinks the pie. Whereas doing the opposite -- transferring money from the top to the bottom -- is the equivalent of throwing Viagra at GDP. It quickly grows the pie. When the bottom 60% get a larger share, everyone greatly benefits, including the top 40%.

The OECD data points to redistributing from the top to the bottom 40%.

The IMF data points to redistributing from the top to the bottom 60%.

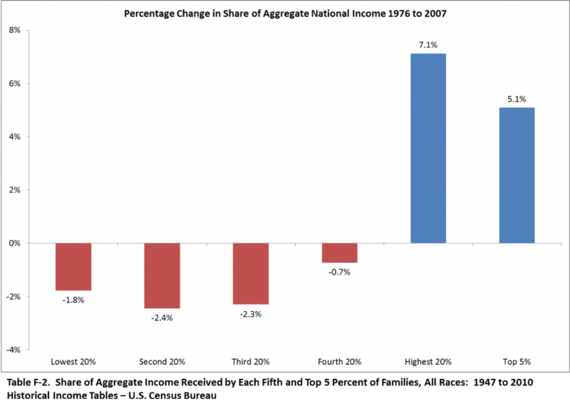

No data points to redistributing to the top from the bottom, which is -- unfortunately for everyone -- exactly what we've been doing for decades. Redistribution actively already exists, and it's in the wrong direction for GDP growth.

The United States: Taking from the working poor and middle classes to give to the rich for 40 years.

So this idea that we should ever let inequality increase because it grows the total pie is completely and utterly false. By letting inequality increase, the entire pie actually shrinks. If we want the pie to grow we need to shift some of that stagnant wealth of the top 20% over to the other quintiles, and the more we shift towards the bottom and middle, the faster the pie will grow for everyone.

"Policies that help to limit or reverse inequality may not only make societies less unfair, but also wealthier." - OECD, 2014

This is a huge reason, if not the best reason, for everyone to support the idea of universal basic income: increased economic growth that benefits everyone. By reducing the rate of wealth accumulation of the top 20% in a way that better distributes that income to everyone else, we see the potential to build national wealth at historic new rates.

A Big Economy

I've estimated before that the total additional cost required to give every adult citizen a basic income guarantee (BIG) of $1,000 per month and every citizen under eighteen $300 per month would be around $1.5 trillion after the elimination of expenses no longer required with a basic income. This is roughly 8.5% of GDP. (Note: the total cost of child poverty alone is 5.7% of GDP)

If that revenue is removed from the vaults of the top 20% where it is sitting stagnant and distributed to the bottom 60% (no need to alter the distribution for the 60-80% according to the OECD or IMF), that's about a 2.83% increase for each quintile combined with the growth from the 8.5% decrease in the 5th quintile. If these are then multiplied by the IMF numbers per 1% increase, the total combined result is a 3.45% growth estimate, for a new total GDP growth rate of potentially 6.44% with a universal basic income in place.

This may sound high, and admittedly quite wonkish, but I believe it's also likely we'll see second and third order effects along the lines of increased productivity, and wage increases through higher bargaining power, which would both result in potentially even larger increases to GDP growth with basic income than the IMF or OECD data points to.