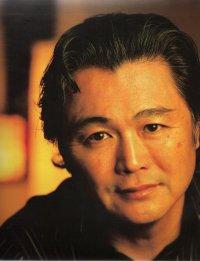

David Mura is a poet, creative nonfiction writer, critic, playwright, and performance artist. A Sansei or third-generation Japanese American, Mura has written two memoirs: Turning Japanese: Memoirs of a Sansei (Grove-Atlantic), which won a 1991 Josephine Miles Book Award from the Oakland PEN and was listed in the New York Times Notable Books of Year, and Where the Body Meets Memory: An Odyssey of Race, Sexuality and Identity (1996, Anchor/Random). Mura’s third and most recent book of poetry is Angels for the Burning (2004, Boa Editions Ltd.). His novel, Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire, will be published in 2009 by Coffee House Press.

David Mura is a poet, creative nonfiction writer, critic, playwright, and performance artist. A Sansei or third-generation Japanese American, Mura has written two memoirs: Turning Japanese: Memoirs of a Sansei (Grove-Atlantic), which won a 1991 Josephine Miles Book Award from the Oakland PEN and was listed in the New York Times Notable Books of Year, and Where the Body Meets Memory: An Odyssey of Race, Sexuality and Identity (1996, Anchor/Random). Mura’s third and most recent book of poetry is Angels for the Burning (2004, Boa Editions Ltd.). His novel, Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire, will be published in 2009 by Coffee House Press.

E. Ethelbert Miller: As a well known Japanese-American writer, do you find yourself looking over your shoulder at economic, political, and cultural events taking place in Japan today?

David Mura: I do pay attention to these matters. But I don’t feel I’m looking over my shoulder — in the sense of being worried that something troubling or unsettling might come up.

I did have that feeling back in the 1980s when the anti-Japanese sentiment here seemed to be reaching a dangerous pitch. Indeed, this became a backdrop to my memoir, Turning Japanese, about a year I spent in Japan in 1985. There were the angry autoworkers in Detroit smashing up Japanese cars and the killing of the Chinese American Vincent Chin by two white men who thought he was Japanese. The Michael Crichton novel and film Rising Sun, with its depiction of a vast Japanese corporate conspiracy bent on taking over America, seems ludicrous now, and even more so the book, The Coming War with Japan. But such predictions were taken seriously back then. All of this went away as the Japanese economic bubble burst in the late 1980s.

I do believe that there is a need in this country, both psychically and politically, to create enemies for the domestic population to focus on, and it’s better if these enemies are of — how might I put this? — a darker hue. For a while, with incidents like the case of Wen Ho Lee (the Chinese American scientist accused of espionage, whose case was dismissed except for one minor charge), it seemed that the target was going to be China. But then came 9-11, and the focus switched to the Muslim world and the Middle East.

By saying there’s a need to create enemies, I’m not saying that there may not be some real threat involved in these three instances — Japanese corporations, Chinese espionage, and Islamic terrorists. I am saying that governments, both ours and other governments, use such threats and often exaggerate them for domestic purposes.

Indeed, the one time recently I was worried about Japan’s international relations occurred when I visited China. The Chinese government was obviously highlighting issues stemming from World War II and Japanese atrocities, as well as the current reluctance of the Japanese government to acknowledge Japanese war crimes. The Chinese government encouraged the demonstrations against Japan as a sort of pressure valve to let off steam from domestic social unrest and divert attention away from governmental repression and economic difficulties within China.

I am somewhat troubled by a few pronouncements lately that indicate that Japan may be becoming more militarily active. I don’t believe such a move would be good either for Japan or for the international community. On the other hand, I still think there is not a great deal of sentiment within the Japanese population for taking on a more extensive, much less a more aggressive, stance in its international relations. And Japan’s very minimal participation in our Iraq debacle has certainly not encouraged the Japanese to think otherwise.

Miller: Are there Japanese words, traditions or beliefs that you attempt to keep alive in your work?

Mura: My feelings about answering this question are rather complex. Instead of giving an initial answer, I think some background is necessary.

I’m a sansei, a third-generation Japanese American, and my grandparents came to this country about 1905. I grew up speaking no Japanese and knowing very little about Japanese culture. In this, I’m not much different from other third generation Americans. The culture of my grandparents was nowhere near as central to my growing up as it was for my parents.

In my case, though, there is one particular difference: Along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans, my grandparents and parents were imprisoned during World War II. The ostensible reason for this was military security. But even the government has now admitted that this was not the case and, in an official apology to the Japanese American community in 1988, acknowledged that the real reasons for the internment camps were wartime hysteria, a failure of leadership, and racism.

For my parents’ generation, the internment camps were something many did not talk about to their children. My own take is that they were imprisoned for their race and ethnicity, and because of this, both their race and ethnicity became explicitly and implicitly something they should not call attention to. This was particularly true for my parents.

Growing up in a largely Jewish Chicago suburb, I wanted to think of myself as white and shunned associations with Japan and Japanese culture. It was only in my late twenties, after reading authors like Frantz Fanon and James Baldwin, that I began to question all this. My trip to Japan and my writing of a memoir about that trip helped precipitate a change in the way I identified myself — as a person of color, as a Japanese American.

And yet, as I’ve said above, I did not grow up knowing much about Japanese culture. I use Japanese words in my writing, particularly in relationship to writing about my family past. Certainly, there are Japanese art objects — posters and woodblock prints, pottery, scrolls, statues of Buddha — in my house. My children have gone to Japanese camp and probably know a little more about Japan and Japanese culture than an average American kid. But jitsu wa, to be truthful, my most real relationship with Japanese culture is one of amnesia — something that has been lost through the process of Americanization and through the political and historical trauma of the internment camps.

In recent years I’ve been interested in the ways Japan, in part through anime and in part through science fiction, has come to occupy a futuristic alternative cultural space. For me, it is almost an alternative reality — one in which my body resembles that of the rest of the population but my mind does not — whereas the reverse is true for me here in America.

Miller: Do you find that many Americans have little knowledge of Japanese internment in the United States during the 1940s? Are you afraid of historical erasure or amnesia?

Mura: I would say when I speak on college campuses only about 50% or less of my audiences — which are self-selecting — know about the internment camps.

The historical amnesia related to the camps fits into a familiar and troubling pattern in the way our culture depicts our history. We are not very inclined to remember the disturbing aspects of our past, particularly when it comes to race. Only a few people know, for instance, that Dillon Myers, who headed the Wartime Relocation Authority, went on after the war to head the Bureau of Indian Affairs, a connection Native Americans might find both expected and revealing.

One key aspect of the internment was the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. Japanese Americans were not given a trial in which they could prove their innocence. We are now seeing similar suspensions or violations of civil liberties today with regard to Muslim Americans. If people were more cognizant of what happened to the Japanese Americans, then people might be more reluctant to suspend civil liberties when dealing with the current threats facing our country. They might think twice and come to conclusion that we should avoid making the same mistakes we have made in the past.

Of course, despite the government’s official apologies to Japanese Americans during the Reagan presidency, there are now conservatives who have tried to argue that the internment camps were justified. But my sense is, if the internment camps and the experience of Japanese Americans were common knowledge, such arguments would be exposed as fraudulent and ignorant and as an attempt to erase or justify a great racial injustice.

I should make clear here that I am not saying that the threat posed by the Japanese American population in 1942 is the exact same phenomena as the threat posed by possible terrorist activity today. These two cases are obviously different. But I do feel that the reluctance to grant non-whites the same civil liberties as whites is still present in America society, and it continues in part because we don’t know our history.

Miller: Could you discuss the cultural implications behind your poem “Minneapolis Public” in your book Angels for the Burning (Boa Editions, 2004)? What does it say about the future of race relations in the United States?

Mura: The poem plays on the image of Minnesota as Garrison Keillor’s Land of Lake Woebegon — i.e., white. Even Chris Rock remarks in his comedy routine, “Minnesota? The only two black people there are Prince and Kirby Puckett.” Yet currently there are 150 first languages in the Minneapolis school system and more than two-thirds of the students there are of color. My poem deals with the school my kids attend. The school has no majority and contains not just black and white kids but kids from a variety of ethnic and racial backgrounds — Somalis, Tibetans, Bosnians, Mexicans, Native Americans — and of course bi-racial kids like my own, who are half-Japanese American, three-eighth’s WASP, and one-eighth Austro-Hungarian Jewish.

In other cities, these various racial and ethnic groups might be more segregated geographically. In my kids’ school, this diverse population has grown up with each other; many have known each other since kindergarten. As a result there’s more interactions between races and ethnicities both inside and outside the school. They go to dances and parties together; they play basketball with each other; they date across races and ethnicities.

This is the future of America. It is part of what makes this country so creative and innovative; it is what makes our culture — as opposed to our foreign policy — so intriguing to the rest of the world.

Of course there are still many problems to be overcome. In high school, as the kids get older, there tends to be more racial separation. The students of color as a whole tend to do less well academically than their white counterparts. There are ironical tensions between native blacks and immigrants from Africa. My daughter’s high school yearbook this year contained memorials to two students killed in gang violence. Meanwhile, conservatives rail against illegal immigration and anything that might be offered their children, in the process forgetting our history of anti-immigrant movements. (Recently, I was asked to do an article about Minnesota for a book similar to one The Nation published over 75 years ago, where Sinclair Lewis observed the presence of those strange new immigrants, the Swedes).

Still the potential for a new future is there. Whether we as a society will pay enough attention to the education and needs of our increasingly diverse population of young people remains to be seen.

Miller: Is it fair to compare a Muslim in today’s military who might not want to go to war against Muslims, with the conflicts faced by Japanese Americans during World War II?

Mura: Such comparisons can be made. Whether they are fair or not depends upon the spirit in which they are made.

During World War II, there were a small number of Japanese Americans who refused to enter the armed services. Some of these, most often kibei who had been educated in Japan, did not want to fight against Japan. But many of these, called No-No Boys for their answers on a loyalty oath given by the U.S. government, saw their answers as an act of civil resistance. They were protesting the government’s actions toward the Japanese American community. (The protagonist of my forthcoming novel, Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire, is the son of one of these men.)

On the other hand, those Japanese Americans who agreed to serve in the armed forces, wanted to demonstrate their loyalty to America. Indeed, the division of Japanese American soldiers, the 442nd, was the most decorated in Europe, and American generals even fought over making this division part of their forces. Japanese American translators were instrumental to the success of the U.S. armed forces in the Pacific theater and the occupation of Japan after the war.

Personally, I feel that the current case of Lt. Ehren K. Watada, who refused to go to Iraq because he believes it is an illegal and unjust war, ought to be seen against the backdrop of this history. His position as a soldier and his actions of civil protest, reflect the legacy both of the 442nd and of the No-No Boys.