(Image: Boston Globe)

There’s a well-established phenomenon in social psychology that states people tend to like things they’re familiar with. Just by the mere practice of being exposed to people or things regularly, our opinion rises and our capacity for empathy increases.

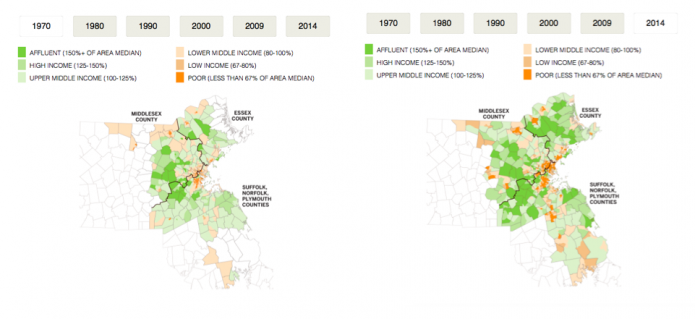

It is with this in mind that new research about income segregation is so troubling. A recent Boston Globe story outlined the rise of income segregation in Massachusetts—wealthy people are increasingly living in wealthy neighborhoods and towns, while the poor are relegated to poor neighborhoods and towns.

This disparity is not unique to Boston, but rather a growing phenomenon across the country according to researchers Kendra Bishoff and Sean Reardon. In the past 40 years, the proportion of Americans living in middle income households has dropped from 65 percent to 42 percent.

As the Globe put it, “Low-income people can go an entire day without talking to someone who has a college degree or a job in a downtown office. And for the affluent, handing a credit card to the gas station attendant or grocery clerk may be their only weekend brush with blue-collar America.”

What happens when the rich and poor literally stop seeing each other?

Empathy breaks down. The plight of the poor becomes an abstract problem not an acute problem if you don’t really see it. This is particularly clear in schools, as sociologist Robert Putnam describes in his recent book, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis.

As Putnam writes, “It constrains our sense of reciprocity. It constrains our sense of what we owe to one another. We are less and less a community.”

The story of an unequal America is not new; we have been becoming increasingly unequal for decades, especially along racial lines. Neither is our willingness to want live in a more equal society. Michael Norton and Dan Ariel’s study, Building a Better America−−One Wealth Quintile at a Time, shows that Americans across the political spectrum have no idea how unequal our economy is. Further, 92 percent preferred a wealth distribution identical to Sweden over what we have in the United States.

One reason for this general lack of understanding about our current inequality is inevitably the fact that our neighborhoods and cities are becoming increasingly segregated by income. This negative feedback loop—more inequality leads to less cross-class empathy leads to more inequality—is what can make positive change feel so intractable. What is to be done?

This question is far too big for one meager blog post, but that doesn’t mean there aren’t answers. Check out the many solutions are offered in our recent eight-part cover story in The Nation, “Game Changers: How we can unrig the rules and reverse runaway inequality”.