It’s bad enough when a person drowns in debt. Shockwaves multiply when a corporation teeters on the verge of failure. The economy becomes even more agitated when a country declares bankruptcy, as Iceland did in 2008 and Hungary and Latvia almost did in 2009.

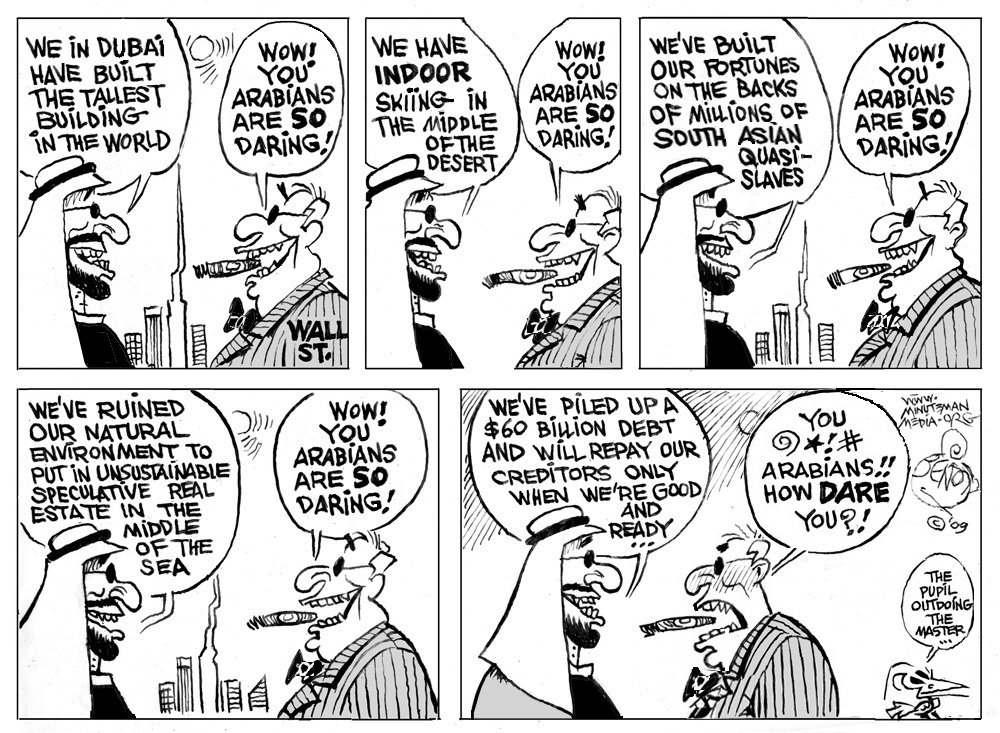

But Dubai? The global economy is obviously still in bad shape if an oil-rich Persian Gulf playground for the wealthy suddenly turns out to be a mirage. This is what happened recently when Dubai World nearly went under. The enormous government-run investment company, which sports the slogan “The Sun Never Sets on Dubai World,” has fingers in many pies, including a Las Vegas casino and Cirque du Soleil.

The Dubai government couldn’t bail it out. After all, Dubai World is responsible for at least three-quarters of the country’s $80-billion debt. The international financial world waited on tenterhooks as the rest of the Persian Gulf stuck its collective head in the sand.

The Dubai government couldn’t bail it out. After all, Dubai World is responsible for at least three-quarters of the country’s $80-billion debt. The international financial world waited on tenterhooks as the rest of the Persian Gulf stuck its collective head in the sand.

Finally this month, neighboring Abu Dhabi plowed $10 billion into Dubai to stave off the creditors. But the signs are still troubling. After all, the story of Dubai World parallels the financial problems experienced elsewhere. The corporation created a huge bubble of real estate, port facilities, transportation ventures and the like. It helped fuel Dubai’s aspirations to host the largest hotel, largest airport, largest fake island and largest theme park in the world, all built by migrant workers who were paid poorly, treated terribly and forbidden to strike.

And Dubai World financed this exercise in grandiosity largely through debt. Dubai is almost tapped out of oil, which accounts for only about 5 percent of the tiny country’s gross domestic product. Dubai World’s latest project, an $8.5 billion casino in Las Vegas, is opening just in time to take advantage of Sin City’s recession-era contraction.

A casino is an apt metaphor for the conglomerate’s operation. Dubai World was gambling with easy credit. It was dazzled by high-rolling investors. And it woke up the next morning with a hangover and empty pockets, hoping that its friends would help it out.

For now, after Abu Dhabi’s largess, the international financial markets are quiet. But sovereign debt — what countries owe their creditors — may be next year’s subprime-mortgage crisis. Greece and Ecuador are in perilous shape. Lebanon and Spain are not far behind.

Then there’s the U.S., which posted a $1.4 trillion deficit for 2009. The demand for U.S. Treasury bonds has dropped, and the value of the dollar may go into the same death spiral that the British pound suffered in the 20th Century. For the moment, our creditors are propping us up. China is too dependent on American consumers’ buying Chinese products to call in its chips. But the day might come soon when the U.S. takes a great fall, as Dubai has done.

If that happens, all Beijing’s horses and all Beijing’s men won’t be able to put the global economy back together again.