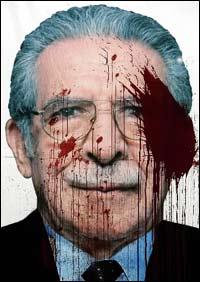

The May 10 genocide conviction of former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was groundbreaking—he was the first former head of state convicted of genocide by his country’s own courts.

The May 10 genocide conviction of former Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt was groundbreaking—he was the first former head of state convicted of genocide by his country’s own courts.

The court found that the army’s atrocities under Ríos Montt—including the extrajudicial execution of 1,771 indigenous Ixil people, mass rapes, and forced displacement—were aimed at destroying the Maya Ixil ethnic group, which the government considered to be an internal enemy and support base of the guerrillas fighting Guatemala’s U.S.-backed regime. Ríos Montt was sentenced to 50 years in prison for genocide and 30 years for crimes against humanity.

But on May 20 Guatemala’s highest court, ruling on appeals filed by the defense, annulled Ríos Montt’s 80-year sentence. The Constitutional Court declared invalid all proceedings that took place after April 19, including the verdict and sentencing. Whether the trial can be picked up again from that date is unclear.

What is clear, however, is that the trial has lifted the curtain on Guatemala’s bloody past. The verdict reached far beyond the question of how a man who once commanded a brutal army will spend his last years.

Judge Jasmín Barrios cited specific incidents in which the army violated not only the basic human rights but also the cultural rights of the Ixil. After the massacres, the Ixil people had to flee into the mountains and were thus prevented from burying their dead and enacting their customary interment rituals. The Ixil’s bond with the land was broken when the army burned their sacred corn. The army, Barrios noted, forced them to leave their land—their world—behind. Survivors who did not flee to the mountains were forcibly relocated to “model villages,” concentration camps controlled by the army. There they were prevented from wearing their traditional garments and speaking their native language.

Ríos Montt maintained his innocence, saying he had no control over what soldiers did in the field. He disputed that there was a policy of extermination; “We had a concept of Guatemalanness,” he said, “not to take away the Maya identity but to consolidate them with us.” As anthropologist Patrick Ball testified, the army wiped out 5.5 percent of the Ixil in 17 months.

As she handed down the sentence, Judge Barrios called on the attorney general to open investigations into others who might have participated in the genocide. She affirmed the cultural and economic rights of the indigenous, long ignored, in spite of specific guarantees in the peace accords that ended Guatemala’s 36-year war. And, as a motive of the genocide, she cited the army’s “defense of the country’s ruling elite.”

Because the verdict touches those who rule Guatemala—and because it affirms the rights of the indigenous in a society where their exclusion and exploitation is still widespread—the blowback has been enormous.

Judge Barrios wore a bullet-proof vest during the course of the trial and, along with the other two judges and the lawyers for the prosecution, received regular death threats. In the courtroom, Ríos Montt’s lawyer, Francisco García Gudiel, shouted at Judge Barrios, “I won’t rest until I see you behind bars!” Barrios was undeterred.

Rallying to the Regime’s Side

Supporters of Ríos Montt mobilized in his defense. Guatemala’s powerful business lobby, the Coordinating Committee of Agricultural, Commercial, Industrial, and Financial Associations (CACIF), went into permanent session immediately after the ruling and demanded that it be annulled, claiming that due process had been violated. But a blog hosted by CACIF sheds light on the business association’s actual concerns: “In the ruling,” wrote Phillip Chicola, “it was argued that the origin of the genocide was racism and exclusion; so the community consultations and the system of quotas will become banners for recompense for those causes.”

The community consultations the blogger refers to are mandated by Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, of which Guatemala is a signatory. Indigenous communities must be consulted, the convention states, before large-scale development projects are undertaken on their land. Almost unanimously, indigenous communities in Guatemala have rejected the hydroelectric dams and gold and silver mines proposed by transnational corporations. In spite of these votes, the projects have gone ahead, with violent repression and retaliations against those daring to protest.

One of the reparations requested by the Ixil victims after the trial was a guarantee to have Convention 169 respected. They also asked for the return of their lands, taken without their consent during the war. The court denied both of these requests but granted a series of others, including an official apology, the construction of monuments, and a mobile educational museum.

“Also, the destruction of the economy and sociocultural fabric of the Ixil was mentioned,” Chicola complained. “In just such a way, access to land, the Rural Development Law, or the Sacred Places will now become rallying points to recompense the damage. Opposing those initiatives will be politically incorrect.” The Rural Development Law has languished in Congress for more than 10 years, although the United Nations has called its implementation a “pending task” required by the peace accords. The Sacred Places Law, which would grant the indigenous people the right to protect areas they consider sacred, is considered by the indigenous to be required by the peace accords, too, as well as by Convention 169. Guatemala’s Chamber of Industry has claimed that the proposed law threatens private property rights.

What Chicola leaves unsaid is this: if the cultural rights of the indigenous are to be respected—as the precedent-setting trial of Ríos Montt suggests—opposing the initiatives above might not be only “politically incorrect” but also futile.

Genie Out of the Bottle

It was clear during the trial that the court was adjudicating not only past events, but also to some degree the present and future. Benjamin Jerónimo, president of Guatemala’s Association of Justice and Reconciliation, was given an opportunity to address the court on behalf of the survivors. “We should no longer have the military in communities, continuing to threaten the Ixil people, the Maya people, the Achí people,” Jerónimo said. “It’s no longer time for that; this is why the Peace Accords were signed—to respect rights.”

But the Guatemalan government has echoed the defense teams’ genocide denial position, suggesting that foreign NGOs had interfered in the trial. Meanwhile, it has ordered an oppressive “state of prevention” in areas where resistance to large-scale development projects is strongest. The state of prevention suspends residents’ rights to strike and demonstrate. To back these measures, the government is wielding a heavy army presence in the streets.

Guatemalan president Otto Pérez Molina has himself been implicated in the genocide, identified by a witness during the trial as responsible for ordering murders and the burning of homes when he was a major in the Ixil area. Pérez Molina will be immune from prosecution as long as he is president, but a recent New York Times op-ed called for the United States government to demand his resignation.

The ripples of Ríos Montt’s sentence have reached across national boundaries, as well. Allen Nairn, who worked as a journalist in Guatemala in the early 1980s, has called for a grand jury to be convened in the United States to indict military advisors and other U.S. personnel who may have abetted the genocide by providing aid, arms, and training to Ríos Montt’s army. Aid was also provided by Israel, Taiwan, Argentina, and Chile.

In Guatemala, at least in some quarters, the country’s elites have been added to the list of the possibly guilty. The Guatemalan Labor, Indigenous, and Campesino Movement has asked the public prosecutor’s office to investigate and prosecute those who benefited economically from the atrocities. The group asked for the return of all that belongs to those displaced by the genocide.

The Constitutional Court’s annulment of the verdict against Ríos Montt is seen as a temporary setback. Shortly after the court announced the annulment, Human Rights Defender Iduvina Hernandez Batres, director of the Association for Promotion of Security for the Study and Promotion of Security in Democracy, tweeted, “Although today the world doesn’t believe it, there are just people in Guatemala and not all of us submit to impunity. We will continue to go after the perpetrators of genocide.”

Reached for comment, Jennifer Harbury, widow of indigenous guerrilla commandant Efraín Bámaca Velázquez, put the trial and any future proceedings in context: “No matter what the courts may do with the technicalities, it’s done—Ríos Montt has been found guilty, and it’s been internationally recognized. The trial broke the silence and it broke the societal amnesia. Everyone heard those women [the indigenous witnesses who testified to mass rape and massacres]. They really can’t put that genie back in the bottle now. It’s the first death knell for impunity for the army.”