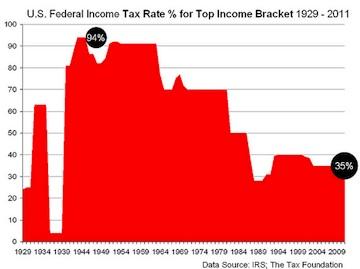

n January, Congress raised the top marginal tax rate on income over $450,000 from 35 to 39.6 percent. But even with this boost, that top federal rate is still less than half of what it was back in the Eisenhower years.

Given the growth of the nation’s debt, we need the rich to contribute their fair share. What to do? Some Democrats in Congress — members of the Progressive Caucus — want to raise the nation’s top tax rate appreciably higher, up to 49 percent on annual income over $1 billion.

But no big-time lawmakers in either party support taxing the rich to that degree.

Republicans typically claim that higher rates would undermine the incentive to work, save, and invest. GOP hardliners even balk at moves to shut tax loopholes. Any step that hikes tax bills, they hold, invites calamity.

Cory M. Grenier/Flickr

Not all these lawmakers, of course, agree on what constitutes a loophole. Many Wall Street-friendly Democrats, for instance, gag at the thought of ending the enormously lucrative tax break for capital gains, the profits from trading stocks, and other assets that flow overwhelmingly to America’s richest.

The bottom line? There’s a bipartisan consensus in Congress on raising top tax rates any higher than their current pre-Bush levels. That consensus: don’t do it.

Few lawmakers dare challenge this conventional wisdom. But their timidity makes no sense. The current consensus against higher top tax rates, as analyst Andrew Fieldhouse details in a study that the Economic Policy Institute and the Century Foundation just released, rests on an amazingly shaky foundation.

Fieldhouse walks us through recent research on top rates and readily demolishes conservative claims that high taxes on high incomes will doom America to economic despair.

Tax rate reductions since the 1970s, the evidence shows, haven’t strengthened the economy. They’ve had “a statistically insignificant impact” on savings, investment, and other factors that drive economic growth.

Fieldhouse also shows — and this may be his most politically significant contribution — that efforts to broaden the tax base and raise top tax rates can and should go hand in hand. He makes that case using the concept of taxable income “elasticity,” economist-speak for how the income taxpayers report may rise and fall with changes in tax rates.

This elasticity — how taxpayers behave at tax-reporting time — depends in large part on the loopholes the tax code offers.

If loopholes beckon at every turn — and efforts to enforce the tax code remain lax — wealthy taxpayers just step up their tax-avoidance ploys when tax rates rise. The IRS ends up collecting less revenue than the agency would have garnered had the wealthy paid what they owed.

By contrast, if Congress seriously went after loopholes — and budgeted for stronger enforcement — wealthy taxpayers would have fewer avoidance options. The revenue collected from higher tax rates would increase.

In sum, Fieldhouse writes, “base-broadening tax reform and higher marginal rates should be seen as complements, not substitutes.”

The payoff if we do both? Oh, not much: just more tax revenue to fund programs that help average American families, a stronger overall economy, and a meaningful pushback against growing economic inequality.

Hiking tax rates on our highest incomes back near the levels in effect decades ago, Fieldhouse’s new study helps us understand, would make wonderful sense economically.

Whether this move ever makes political sense to America’s lawmakers depends, of course, on the rest of us — and the political pressure we choose to bring to bear.