On Wall Street, they’re giving Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer the bum’s rush. Ballmer has just announced he’ll soon retire. After his announcement, Microsoft’s shares shot up 7 percent. The wise guys on Wall Street obviously can’t wait to see Ballmer go. And neither can business pundits. Ballmer’s 13 years at Microsoft’s summit, they seem to agree, have been a huge disappointment. Evidence certainly does exist to back up that appraisal. Microsoft, once a pacesetter, has become a second-tier presence in the hot new frontiers of mobile and cloud computing. Under Ballmer’s watch, Microsoft’s share price has dropped by about a third. Meanwhile, Ballmer himself has done fabulously well. The value of his own personal Microsoft stock stash has jumped since 2000 — after years of lavish executive rewards — by more than $3 billion. Few business observers believe Ballmer merits these billions. But Ballmer’s pals feel he’s performed just fine. On his watch, after all, Microsoft’s annual revenue has almost quadrupled.

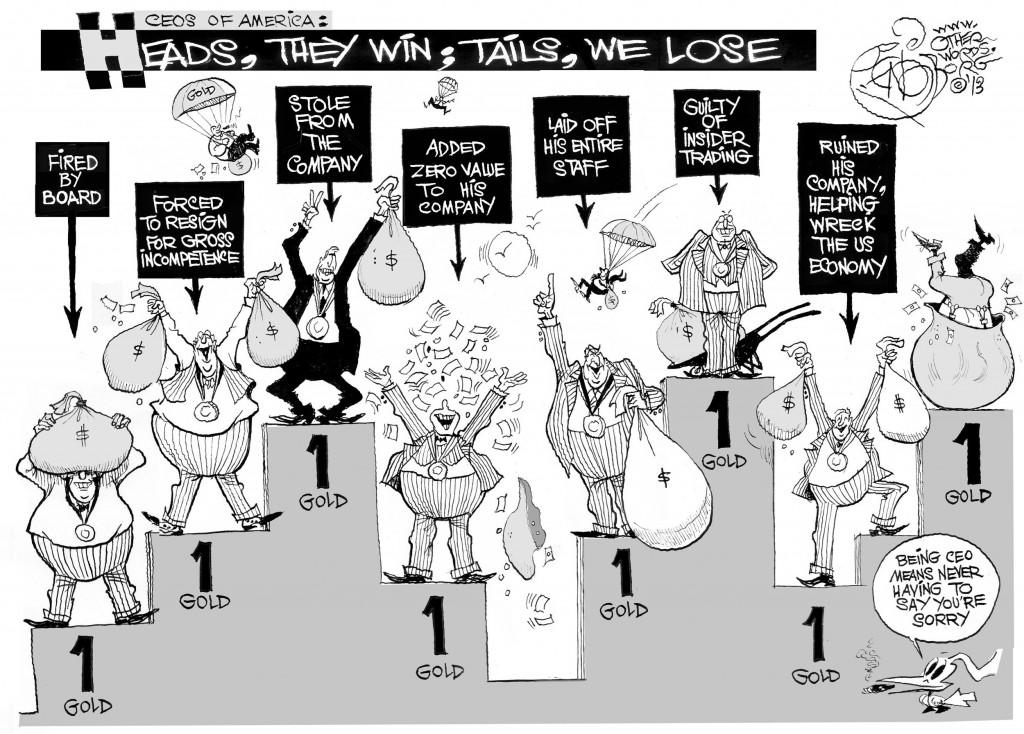

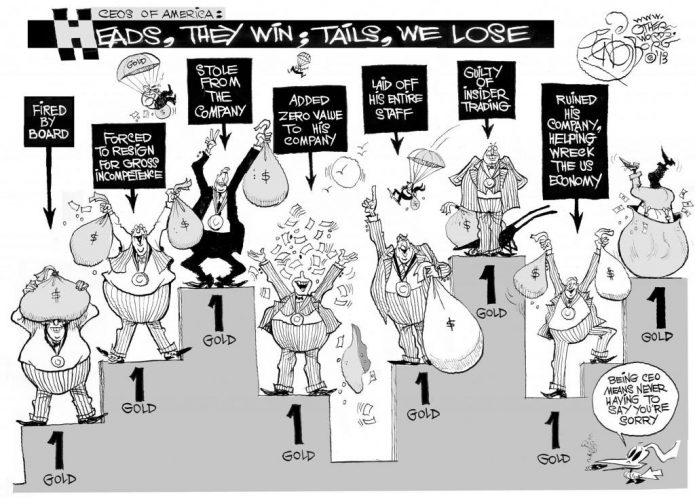

Heads They Win, Tails We Lose, an OtherWords cartoon by Khalil Bendib

And that share price skid? Over the past 13 years, other computing giants have done much worse than Microsoft. Cisco shares have slid 54 percent, Dell’s almost 70 percent. So what should we make of all this? Has Steve Ballmer performed well or poorly? You could make a case either way — and that answer doesn’t just go for Ballmer. America’s CEOs, even the most hapless among them, can always point to some “metric” that illustrates how well they’ve “performed.” Sarah Anderson and her colleagues at the Institute for Policy Studies — of which I’m one — have been tracking this “performance” charade for the past 20 years. Over those years, the Institute’s annual Executive Excess reports have shown repeatedly that America’s CEOs owe their outrageous pay to outrageous behaviors, everything from downsizing to worker benefit rollbacks. Corporate America, naturally, disagrees. High executive pay, corporate leaders insist, simply reflects high performance. This year’s just-released, 20th anniversary Executive Excess report puts this claim to the test — by measuring America’s most highly paid CEOs of the past 20 years against a performance yardstick that even the most inventive corporate flack can’t game. This performance yardstick starts with bankruptcy. CEOs who’ve led their companies into collapse — or only averted collapse because taxpayers bailed them out — have clearly performed poorly. So have CEOs who end up getting fired. And so, as well, have CEOs whose companies have had to shell out significant sums in fraud-related fines and settlements. No CEO who has been “bailed out, booted, or busted,” as the new Executive Excess report puts it, can possibly be considered a “high performer.” How many of America’s most highly paid CEOs of the past 20 years fit this “poor performance” definition? The new Executive Excess has done the calculations, using the Wall Street Journal‘s annual lists of America’s 25 most highly paid CEOs as a source. Of the 500 places on the last 20 of these lists, Executive Excess 2013 finds, nearly 40 percent have been occupied by CEOs who went on to be “bailed out, booted, or busted.” An even greater share of highly paid CEOs — 100 percent — has enjoyed a subsidy from America’s taxpayers. The more corporations pay their CEOs, under current tax law, the bigger their tax break. Executive Excess 2013 highlights the pending legislation that would undo this tax subsidy — and also lists other steps that could help rein in CEO pay excess. We could, for instance, deny government contracts to companies that pay their CEOs over 25 or 50 times worker pay. Back in the 1960s, hardly any CEOs took home more than 50 times what workers did. By 1993, CEOs were averaging 195 times worker pay. The current average differential: 354 times. “This scares us,” we conclude in Executive Excess 2013. “What scares us even more: the thought that unless regulators, lawmakers, or shareholders do something to stop this madness, 20 years from now today’s corporate compensation will seem as modest as the pay levels of 1993.”